University of Nebraska–Lincoln researchers released a decision-making tool this month to guide land managers and owners on the best use of time and money to resist, accept or direct tree invasions on grasslands. In the July 2025 issue of Journal of Environmental Management, they and University of Montana–Missoula researchers described how they adapted a tool used in managing ecosystems, the Resist-Accept-Direct Framework, for use in grasslands.

Rheinhardt Scholtz, the main author of “Reconciling scale using the Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) Framework to improve management of woody encroachment in grasslands” said trees like redcedars pose slow but serious threats to grasslands. He and the other researchers used funding from the federal government’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research to develop ways to gauge, track and tackle the growing problem.

“Now we realize that the threat of woody encroachment is way larger than we could think,” Scholtz said. “We would stand on a landscape, and think, ‘I don't see any trees around. We’re safe.’ But as you start walking around, you see little seedlings, and they start growing and growing. All of a sudden—boom!—you've got these large, seed-bearing adults now spreading seeds all around, and the threat becomes very real and the problem gets out of control very fast.”

Redcedars encroaching on grasslands threaten the livelihood of ranchers and the beef supply. Such trees harm grasslands in many ways, like reducing wildlife and available water and increasing wildfire risks and vector-borne diseases. Over the past few decades, entire grasslands in the United States have flipped to woodlands. The trees now threaten the Nebraska Sandhills, one of the world’s last seven largest continuous grasslands, as identified by Scholtz and Dirac Twidwell, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln agronomy and horticulture professor.

The team of researchers used the Rangeland Analysis Platform and the power of Google Earth Engine to detect shifts in boundary lines between trees and grass across the United States over time. With the platform, they screened land in 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2020 and labeled shifts they detected as “early warning signals” of a transition from grassland to woodland.

They looked at land at six scales of size. The smallest plot of land showed up on the computer at 3x3 pixels, with each pixel corresponding to 240 meters. So, one 240-meter pixel surrounded by eight 240-meter pixels corresponded to about 52 hectares or 128.5 acres. The other five scales were 9x9, 27x27, 81x81, 113x113 and 139x139 pixels. The largest scale looked at, 139x139 pixels, corresponded to about 111,289 hectares or 2,750,009 acres or 4,297 square miles. This is larger than the average U.S. county at 1,208 square miles.

Researchers analyzed each pixel on the computer in reference to its six concentric scales and developed maps showing whether transition was occurring at any of the scales. The researchers left out cropland, water bodies, urban areas and areas historically forested from their analysis.

They labeled each pixel with a number from zero to six, telling how many of its scales showed early warning signals of transitioning to woodland. A pixel labeled zero had no scales showing early warning signals, but a pixel labeled six had all scales showing early warning signals.

Researchers then used the RAD Framework to classify areas with no scales or one scale showing early warning signals as “resist” areas. Here, people would have the best chance to resist a shift to woodland and make the best use of their time and money in doing so. Researchers labeled areas with two to five early warning signals as “direct” areas. Here, people could strive to direct the change to a still beneficial land state. Areas with all six scales showing early warning signals were deemed “accept” areas where people probably needed to accept they were unlikely to prevent a transition.

Daniel Uden, a resilience spatial scientist at Nebraska, said the framework does not tell people what they have to do but gives them a tool for thinking through how best to use their resources to address the problem.

“There are a lot of uncertainties that come in related to how we respond to change on the land, and this helps us do it,” he said. “It's a starting point, really, for responding in a structured way. Hopefully, it empowers people to manage transitions on their land.”

Researchers took their analysis a step further by compiling land plots to look at 14 ecoregions in the United States. They saw that ecoregions in the southern and eastern Great Plains suffered the most transition to trees and would be unlikely to resist it. Ecoregions in the north and western Great Plains, like the Nebraska Sandhills, had the least tree invasion and the best opportunity to resist it.

Uden said tackling the shift in vegetation is challenging because it is occurring over large areas over long periods of time. Generally, northern and western ecoregions show the boundary line of trees moving out from patches, like windbreaks. The central and southern ecoregions show the spread of trees moving from east to west.

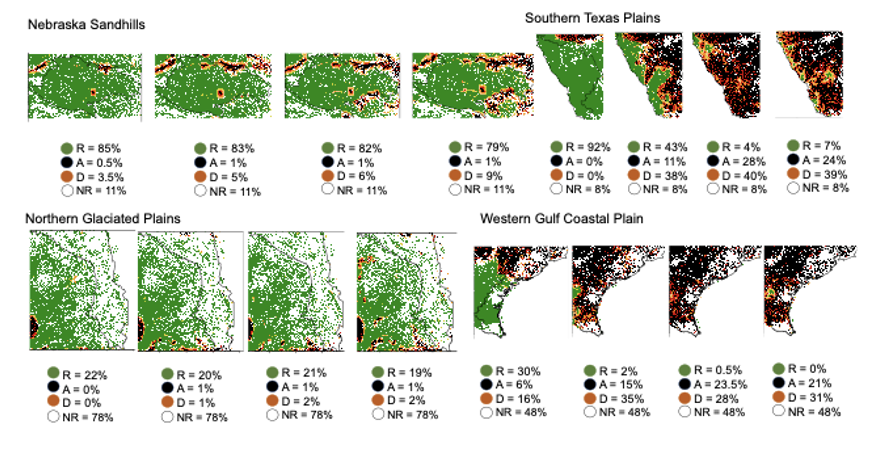

Researchers could zoom into individual regions, like the Nebraska Sandhills and Southern Texas Plains, and view four computer images, from 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2020, of grasslands and possible tree invasions. Green areas show grasslands without warning signals of trees moving in. Here, researchers suggest people can resist (R) a change to woodland. Black areas have enough trees already established there that people may have to accept (A) that change. Red areas also have trees, but researchers suggest people may be able to direct (D) the change. White areas are not rangeland (NR) but are cropland, water bodies, urban areas or areas historically forested.

“We wanted to monitor how each phase of the RAD Framework is changing over time across the biome,” Scholtz said. “And so, for example, the results from 1990 to 2020 show that the ‘resist’ areas started at 84% and dropped down to 60%, so that's a 24% decline over three decades in areas where we could be proactively managing for this transition.”

About 79% of the Sandhills remain in the “resist” state. As the most intact prairie in North America, the Sandhills ecoregion is an example of land that people should prioritize to keep in a resist state, Scholtz said.

Attempting to resist transition everywhere doesn’t work, he said.

“We've seen that,” he said. “It's a failed methodology. We'll never win. We'll never beat nature in that type of thing. We have limited resources, limited funds.”

Instead, he suggested acting more proactively and quickly by not planting aggressive encroachers like redcedars. In the past, people commonly planted redcedars as windbreaks, and the trees have spread from there.

To stop spread at the beginning stages, people often use mechanical removal or chemicals, but Scholtz said other research has shown fire to be cheaper and more effective.

Next steps he listed for this research would be developing and updating the online monitoring tool regularly, perhaps every five years. He said he would like to house it on a website to engage more landowners in using the tools for their own benefit.

Uden has already begun instructing his students in classes like Great Plains Ecosystems on the use of the RAD Framework. He said his hope is to equip future biologists, ranchers and farmers with more than an understanding of the change on the land and why it’s happening by giving them a whole toolbox of ways to respond to the change.

“Part of what the tool does, I think, is show us how we're all connected and how this is a large-scale issue that's happening, not just in Nebraska and not just across the Great Plains, but even globally,” he said. “If we think about this as an issue that's happening not just on my property but across the state and the Great Plains, then we see how it's necessary to work together to address these challenges.”

He suggested future research in the area might focus on the economics of battling the shift in different places over time and the outcomes of that work. Researchers could also continue to refine the resist-accept-direct categories for tree invasions in grasslands and their recommendations of responses, he said.

Besides recommendations to respond to encroachment threats faster and prioritize areas, Scholtz said the research led to a message of hope.

“There are lots of parts of the biome where we have a significant opportunity to resist this imminent change that's been here since the mid-1900s, and we can do something about it,” he said. “It's not our destiny that we lose the Great Plains in the next 100 years. So, we got to act fast enough so that we can actually keep it grass side up for our next generation.”