Lincoln, Neb. —Jenny Dauer, associate director for undergraduate education in the School of Natural Resources, received a $400,000 National Science Foundation grant this fall to look further at how the Science Literacy 101 class can encourage civic engagement in undergraduate students.

This is the third Improving Undergraduate STEM Education grant she has received for the class as the lead instructor in the past six years. She also received a National Science Foundation Core grant from 2019-2023.

“I feel really excited about this grant because it's an important area to expand our capacity as science educators,” Dauer said. “There are very few classrooms that have the opportunity to pursue interesting questions like what we do in Science Literacy 101 because they're obligated to talk about particular content, but we're free from that. We can focus on skills that prepare students to be problem solvers and make differences in their communities.”

All students in the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources are required to take Science Literacy 101: Science and Decision Making for a Complex World. About 600 students take it each year under a cross-disciplinary team of professors and postdocs led by Dauer.

The course focuses on broad skills like decision making, information literacy and systems thinking to foster the attributes that CASNR has designated as key for its graduates. These attributes are the ability to engage diverse perspectives for personal and professional success; solve problems with validated evidence, systems thinking and responsible stewardship; and impact communities and the world through service, civic engagement, entrepreneurship and leadership.

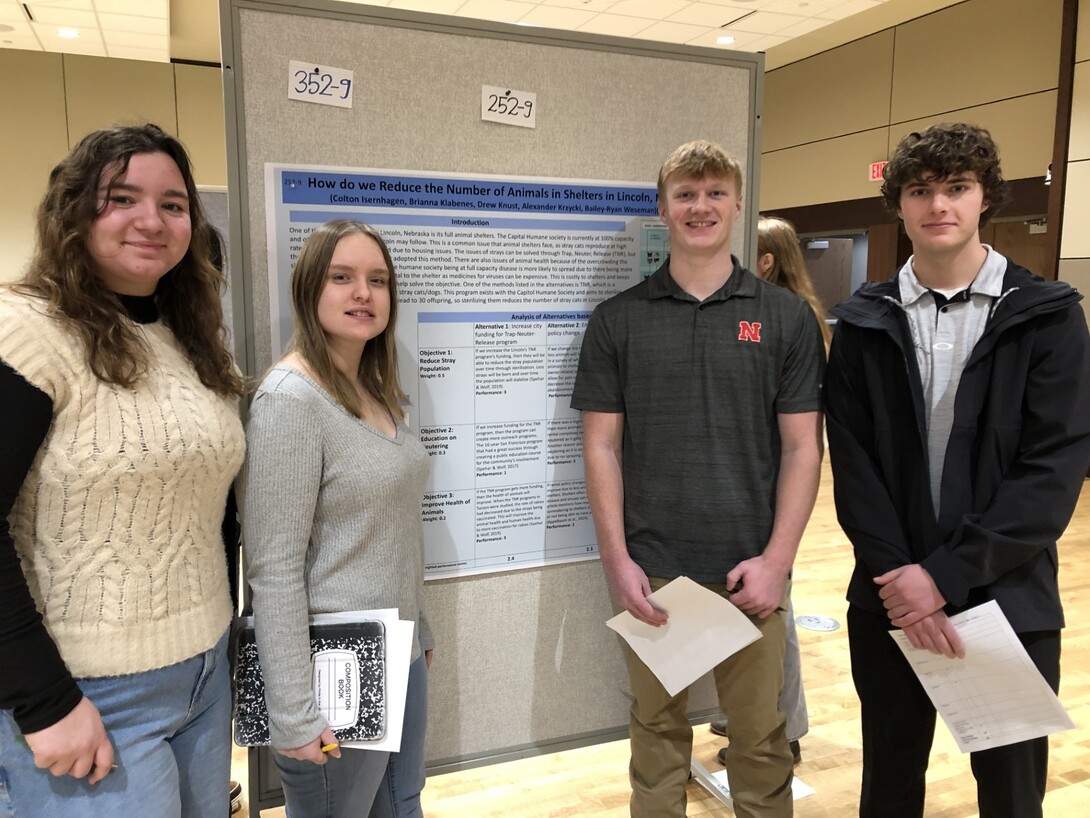

In leading the class and designing curricula for it, Dauer has strived to offer students real-world experiences to learn from. She walks students through a scientific process of seeking and weighing possible solutions for issues like plastic pollution, sports concussions and water conservation. In the last third of the class, students work in small teams to pick an issue they’re interested in, go through the decision-making process they learned in class and create a poster with their results.

The students must also connect with someone from the community working on the issue and spend four to six hours in related activities. Past students have taken actions like planting trees on campus, touring a hydroponics farm, attending farmer co-op meetings and spraying knotweed along riverways.

The instructors have started a list of past community partners willing to help students in future projects. Dauer said they will use the IUSE grant to further develop the experiential learning parts of the class and to study their impacts on the students and whether students feel motivated and capable of making a difference on issues in their communities.

She said she also sees other science education researchers as possibly benefiting from what her team has learned in offering students experiential learning.

“We hope that other universities can learn from our model and be inspired to think about doing things like this in large-enrollment courses,” she said.

Given artificial intelligence and all the information available to people in the 21st century, Dauer said educators need to understand what skills students really need when encountering problems related to science. Rather than just technical knowledge, she said students need to understand how information is produced and feel confident they can find it and apply it.

“They can navigate the problem and understand the role that science plays but, also, science doesn't give us the answer,” she said. “We need to integrate science with our values and to be able to navigate that complexity. I think that's more of what we need to foster in students now, compared to 50 years ago.”

Still, many universities continue giving students introductory STEM courses without the students receiving a chance for real-world experiences until near the end of their college career with a capstone course or internship, Dauer said.

“The problem with that is that students don't get to see why they're learning the things that they're learning and don’t get to see content in an integrated way,” she said.

Added to that, some students, especially first-generation college students, are unaware of how they can take part in research, internships or extracurriculars, she said. They miss out on this “hidden curriculum,” she said, and get less from their college experience and degree.

She and the other instructors in the class are trying to counter some of that in this introductory science literacy course with the real-world experiences they offer. The other instructors are Christine Haney Douglass from the college’s honors program, Michaella Fevold from animal science, Louise Lynch-O’Brien from entomology, Brandi Sigmon from plant pathology, Megan Sindelar from agronomy and horticulture and rotating postdocs.

The research team is researching how well the class model works and will continue to do so with the latest IUSE grant.

“In some of our research, we've seen students really gravitate towards thinking about their impact on communities primarily through education or talking to others or posting on social media about them,” Dauer said.

She said she would like students to move past solely talking about issues to actually doing something about the issues, like voting, writing letters to legislatures, making donations, showing up at meetings and making personal choices that make a difference.

“I want to see how much the experience of thinking critically through evaluating evidence around an issue while simultaneously getting involved in a community that’s doing something about it might change students’ perception of what they personally can do and how their skills could be important,” she said. “And students will see the complexity and nuance of these issues and how difficult they are to solve.”

The Science Literacy 101 class pushes the boundaries of what is considered science education, and the latest IUSE grant allows her to think about how it can continue to do so, she said.

“I think science education needs to be more than textbook learning, more of, why do we need science?” she said.