Lincoln, Neb. — University of Nebraska-Lincoln graduate student Mackenzie Batt’s research found a mutation in cattle that causes exercise intolerance and poor meat quality.

Batt is a doctoral student from Lincoln studying biological sciences. She completed her undergrad at Nebraska Wesleyan University where she discovered a joy for research and got connected with UNL professor Jessica Petersen. Batt did not have much experience in the beef industry before her work with Petersen, but Batt has enjoyed learning about and making an impact in the industry.

After graduation, Batt is considering continuing her work in the animal science industry, possibly in product development.

Research and impact in the beef industry

During her master’s research, Batt and the team studied a cattle herd at Gudmundsen Sandhills Laboratory where certain calves were reported to have exercise intolerance. After exertion, the affected calves would sometimes collapse for a few minutes and get back up while others would not survive. One thing these calves had in common was the same bull in each of their pedigrees.

“We traced this mutation back to a purebred bull, and we found that this bull was in the pedigree of 200,000 other members of that breed,” Batt said.

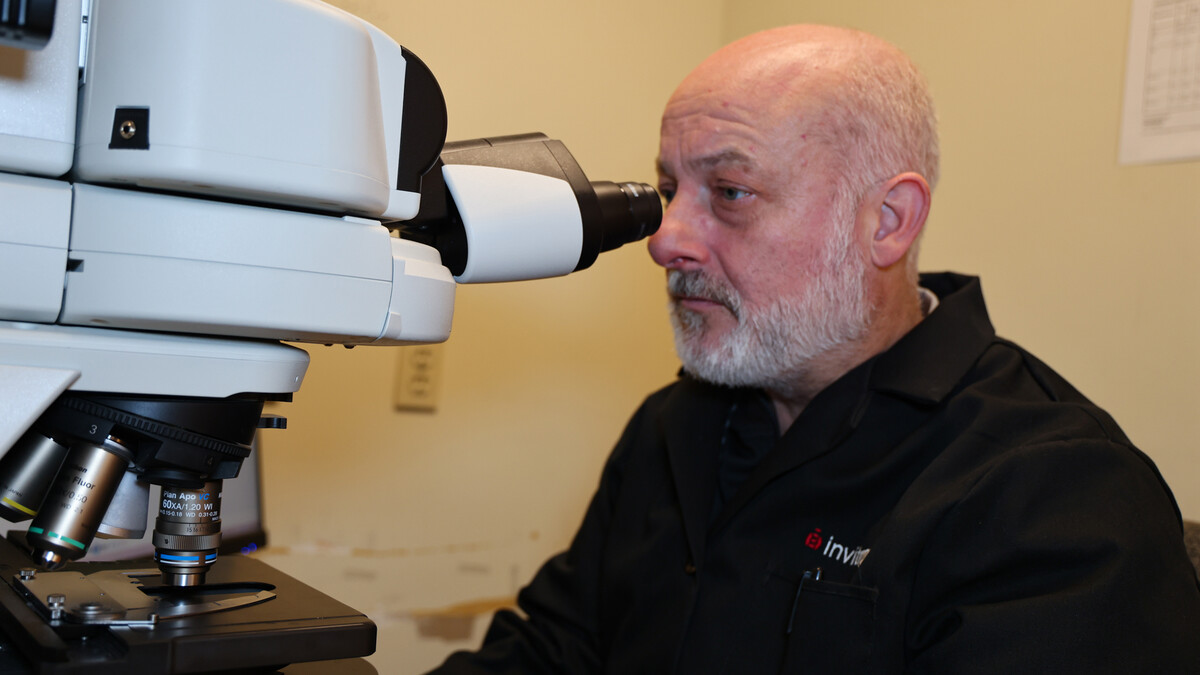

From there, the team analyzed the genome sequences of affected and unaffected cattle in the herd and was able to identify a mutation within the PYGM (glycogen phosphorylase) gene on chromosome 29.

PYGM is responsible for producing the enzyme that breaks down glycogen, a sugar, into a usable source of energy for cattle. This enzyme is absent in cattle with this mutation, making them fatigued easily.

After harvest, when the body is unable to break down glycogen the mutation prevents the pH from decreasing in the meat, shortening the shelf-life. As a result, cattle with this mutation are also dark-cutters, a term used to describe the darker appearance of their meat. Meat that is dark red or almost purple is not as appealing to consumers as cherry-red meat. That, combined with the shorter shelf-life reduces the value of the meat produced by the carcass.

By tracing and identifying carriers of this mutation, these cattle can be prevented from breeding and further spreading the mutation. Development is in progress for a genetic test that producers can use to identify if an animal is a carrier.

Batt said this was a collaboration across genetics, meat science, veterinary medicine and other segments of animal science in UNL and beyond. She was grateful for the opportunity to work with Nebraska researchers Jessica Petersen, Matt Spangler, Gary Sullivan and Travis Mulliniks (now with Oregon State University), and Stephanie Valberg from Michigan State University and David Steffen with Nebraska’s Veterinary Diagnostic Lab. She also worked with UNL graduate students Leila Venzor, Rachel Reith and Nicolas Herrera.

Challenges and opportunities

According to Batt, there are many opportunities for finding ways to improve animal health and efficiency. However, it can be challenging to find these ways.

One of these opportunities lies in studying the mitochondrial genome and its connection to growth characteristics and efficiency. Batt will focus on this topic for her doctoral research. According to Batt, the mitochondrial genome is often ignored in beef cattle production and selection.

“Traditionally, breeding programs have concentrated on choosing bulls with the most desirable traits,” Batt said. “This project aims to highlight the importance of also considering the genetics of the cows, since mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited solely from the mother, plays a critical role in energy production. Therefore, selecting the best cows based on their mitochondrial genotype could enhance breeding outcomes.”

These enhanced breeding outcomes could improve the productivity, profitability and health of cattle.