Lincoln, Neb. —It may have been 30 degrees out with eleven inches of snowfall on the ground from the day before. But in the Nebraska Innovation Campus greenhouse, it was in the mid-70s — the perfect temperature for plant experiments.

That day in February, students from Dawes Middle School were learning how to set up an experiment for success. The topic in question: seeing how pea shoots would fare in lunar soil.

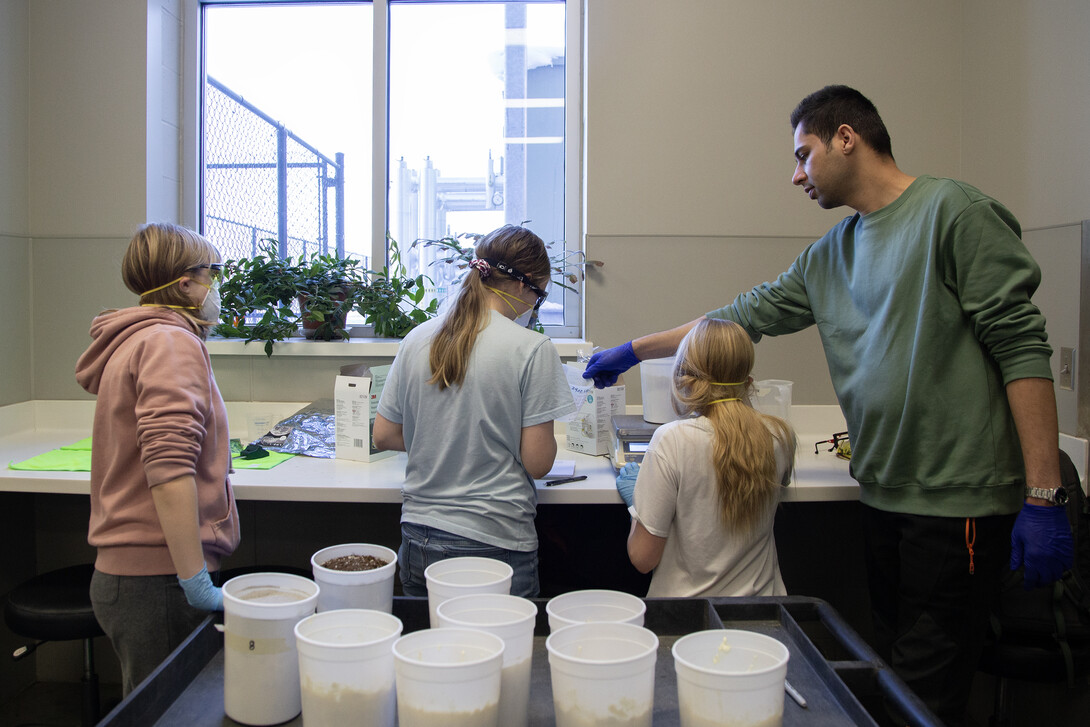

First, they mixed standard soil with a lunar soil simulant in different ratios, making sure to carefully measure and label everything. Then, they created divots in the soil and dropped pea seeds inside. The seeds got a set amount of water before getting stored in the greenhouse.

Complex Biosystems graduate student Cassie Palmer hopes that these tiny seeds will help students see the bigger picture when it comes to the scientific method and lab work.

“For them to not only understand coming up with the big picture and all the details is kind of the goal of this,” she said.

The project was based on Palmer’s own lunar soil experiment. She works alongside Biological Systems Engineering graduate student Ehsan Fazayeli, who is in charge of research.

They have been meeting regularly with Dawes and Lincoln Northeast High School to share a hands-on version of science. It’s part of the Plant the Moon Challenge, a program from the Institute of Competition Sciences in collaboration with NASA. The overarching goal connects with NASA’s Artemis program, which intends to get humans back on the Moon for the first time since the 1970s.

Plant the Moon aligns perfectly with a dream Palmer has had since childhood: working for NASA. After starting her college career in engineering, she switched to and eventually earned her Bachelor of Science degree in bioinformatics. It’s an area of research that uses computer programs, softwares and databases to keep track of biological information.

Palmer believes her area of research could help reduce costs, labor and time to make space agriculture practices more efficient.

“When the opportunity came up … and I became familiar with the NASA Artemis program, I thought, ‘Wow, this is setting me on track for all of my dreams.’”

Cultivating young minds to solve grand challenges

Their work also ties into the SPACE2 program: Space, Policy, Agriculture, Climate and Extreme Environment. It is funded by the UNL Grand Challenges Initiative as one of 10 planning grant teams.

The SPACE2 team is an interdisciplinary mix of 14 faculty involved in areas including engineering, law, food science, computing and media arts. More faculty will join the team as research progresses.

Fazayeli’s focus is on engineering challenges such as handling resource efficiency, self-sufficiency and high-stress environments in space. Potential solutions could include resource-constrained food production, closed-environment agriculture, oxygen generation and recycling.

Exploring agricultural possibilities in space has not historically been a major focus of space travel, and the group aims address this important issue, Fazayeli said. Delivery costs, mental health considerations and fresh nutrients are all reasons space agriculture is crucial.

“So far, packaged foods have been the main source of nutrition for astronauts and crews. When you look at the long-term mission, that is not logical,” he said. “Crews need to have greens.”

To design the experiment for middle and high school students, Palmer first developed her own soil simulant project using soybeans. She used a lunar soil simulant from Exolith Labs, an organization largely funded by the Florida Space Institute at the University of Central Florida. It’s a compound that closely mimics the fine-grained covering of rocks and minerals on the moon’s surface.

After using image analysis software to understand how the soybeans reacted to the simulant, Palmer worked to create a school-friendly version of her process. The schools have gardening clubs, and the students were enthusiastic about taking on this extraterrestrial challenge. About two dozen students total participate.

This project differs in that the students can use up to half regular soil in their pots, and they chose pea shoots since it will be an easier crop to work with.

“It’ll make it a lot easier for them to see the effect over time and compare different harvests,” Palmer said. “With soybeans, it takes a lot longer for those plants to grow so the change is not as noticeable.”

The pea shoots should grow over the course of eight weeks. The students will be able to gain research skills as they watch the plants grow, Fazayeli said. By the end of the project, students should be able to determine which soil simulant mix produces the best yield. They will also learn ways to efficiently use resources like water and nutrients.

The benefits of involving students in this project include helping to cultivate young minds and getting fresh perspectives, he said.

Through this project and his research efforts, Fazayeli hopes he can help solve the large, multifaceted problems of growing crops in space. While the University of Florida reported growing plants from lunar soil for the first time in May 2022, many challenges remain.

“I hope I can be a part of a team finally to find a solution to solve the problem of space agriculture,” he said. “I want to grow plants on an extraterrestrial environment — because at the moment we are at the very first stage of this research.”

As he makes progress on his research, Fazayeli also wants to delve into phenotyping and robotics, because nearly everything in space will have to be remotely controlled.