Aug. 29, 2013

LINCOLN, Neb. — Grain sorghum lipids lower cholesterol levels and intestinal bowel inflammation in lab animals, University of Nebraska-Lincoln research has found, and scientists are working to figure out exactly how in an attempt to create food products that could manage both conditions in humans.

The research is part of UNL's emphasis on "functional foods," which are dietary systems containing natural agents designed to impart certain health benefits, including prevention of a variety of diseases. The work involves scientists from several disciplines.

Reducing LDL cholesterol is a key strategy to reducing coronary heart disease, which is a major cause of death in the United States and other countries. Statin drugs are effective and widely prescribed, but they are expensive and can have serious side effects. Moreover, inflammation of the bowel has been linked to many instestinal disorders, including colon cancer. Scientists from UNL and elsewhere are trying to find nondrug strategies, such as functional foods, to replace drugs.

That's where grain sorghum comes in, said Vicki Schlegel, UNL food scientist and part of the research team. It is a rich source of several chemicals that can decrease cholesterol in addition to preventing inflammation but has been largely overlooked for human consumption in the U.S. Although the U.S. is the world's leading producer and exporter of grain sorghum, most of the crop in this country is used for animal feed and ethanol production.

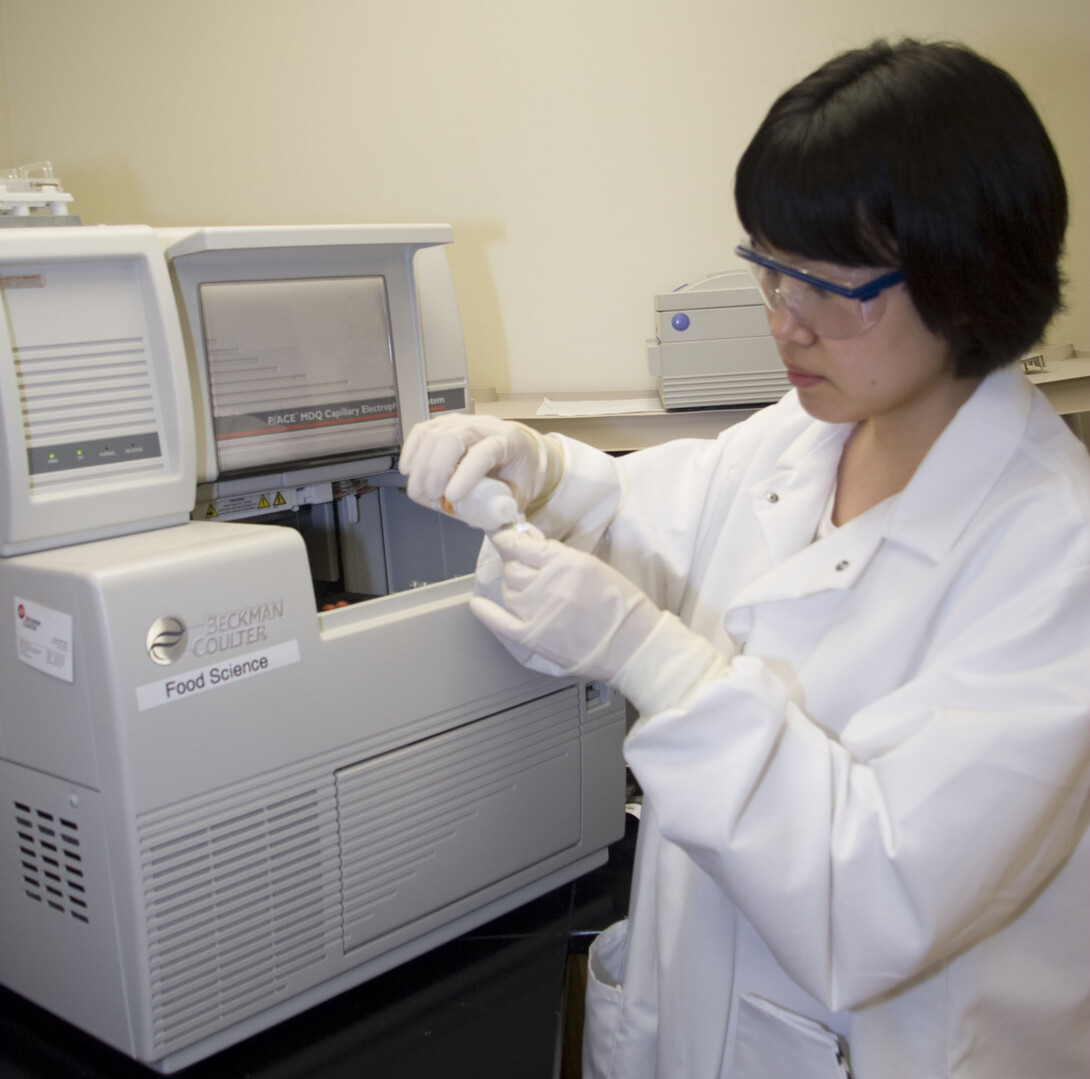

The UNL research focused on the extractable lipid fraction of grain sorghum whole kernels and their effect on cholesterol metabolism in hamsters, which have similar lipid cholesterol metabolism as humans.

Scientists found that hamsters fed a diet supplemented with grain sorghum lipids had significantly lower cholesterol and liver cholesterol levels, Schlegel said.

"These concentrations were in the metabolic ranges known to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease in humans," the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources scientist added. "They probably prevented cholesterol from absorbing through the large intestine. It just passed through.

"We also recently determined that the fatty diet fed to the animals not only increased cholesterol but also intestinal inflammation. However, sorghum supplementation was able to remediate many markers of this cellular stress. How it does this, well, that is the next step in our research," Schlegel added.

Ongoing research includes determining the specific components responsible for both responses. Then, scientists hope to incorporate those into a food ingredient for humans.

In addition to its human-health implications, such ingredients also could raise the value of sorghum for producers, Schlegel noted. Although the UNL research focused on whole kernel sorghum, the components responsible for these health benefits also can be extracted from sorghum-ethanol byproducts, which would improve the economics of that ethanol production since those byproducts now are used, if at all, as animal feed.

This research is funded by the Nebraska Grain Sorghum Board, United Sorghum Checkoff Program, and UNL's Agricultural Research Division.

Vicki Schlegel, Ph.D.Professor

Food Science and Technology

402-416-0294

vschlegel3@unl.edu Dan Moser

IANR News Service

402-472-3030

dmoser3@unl.edu