Lincoln, Neb. —Inspired by an extension event survey comment, Dr. Bijesh Maharjan, Associate Professor & Extension Specialist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Panhandle Research, Extension, and Education Center, conceptualized the soil health cycle (SHC) as an iterative soil health management cycle to achieve agricultural sustainability.

“The term 'Soil Health Cycle' was shared by a participant during the 2023 Nebraska Soil Health School event at UNL Haskell Ag Lab in Concord, NE,” Maharjan said. “It was mentioned in an anonymous survey comment but without further explanation. Intrigued, I searched for it online and found its brief mention on Corteva Agriscience's website. This sparked a collaborative effort with my co-authors to develop the concept further, leading to our now-published manuscript.”

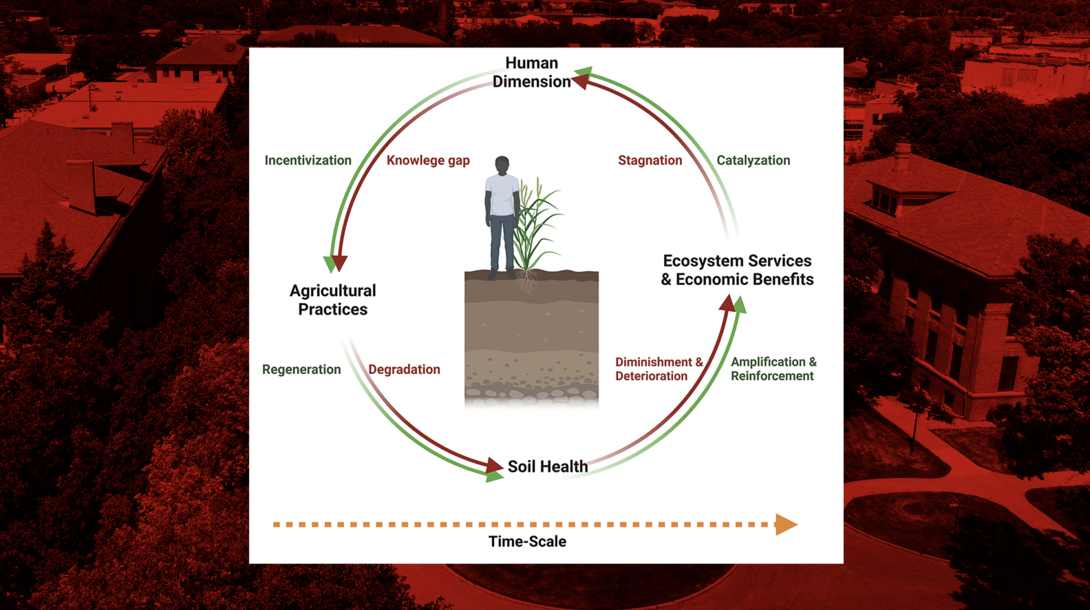

The Soil Health Cycle (SHC) is a feedback cycle in soil health management comprised of a series of interdependent entities and steps that involve human dimensions affecting decisions on agricultural practices, their impact assessment, and making inferences to iterate the process accounting for site-specific resource constraint and complex agroecosystems to achieve iterative soil health improvement. In contrast to soil nutrient cycles, where a specific nutrient, its transformations, phases, and transport pathways through soil, plants, microbes, and environment are explored, the SHC is more analogous to management cycles such as the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle, which provides a structure for iterative testing of changes to improve quality of systems.

The SHC offers a systematic approach to integrating soil health practices, measuring soil health benefits due to soil health management in terms of productivity, profitability, and environmental benefits and their cumulative impact on policy, economic factors, and human dimensions, which sets the cycle revolving. The cycle consists of four interdependent components: (a) Human Dimension, (b) Agricultural Practices, (c) Soil Health, and (d) Ecosystem Services and Economic Benefits (Figure 1).

“In essence, comprehensive soil health management involves several interdependent components and each of them is crucial for achieving agricultural sustainability, “ Maharjan said, “and it will be an iterative process over time.”

“In addition to presenting and justifying the feedback cycle in soil health management to achieve iterative soil health improvement, we also reviewed scientific literature determining the current state of research on the effects of soil health practices on soil health indicators (SHIs) and soil function outcomes—a key piece in the feedback cycle,” added Maharjan.

There has been a growing body of literature on soil health over the past two decades. Evaluating the impacts of soil health practices on SHIs is a preliminary step in our efforts to enhance soil health practice adoption. The confidence in the causality of improved SHI can be increased by demonstrably linking them to soil functions such as productivity, sustainability, and profitability. Such presentations will inform policy, incentive programs, and initiatives affecting the human dimension to adopt and sustain soil health practices. Therefore, besides reporting SHIs, soil health experiments, and reports should include one or more of the soil function benefits, specifically crop productivity (for food security), environmental quality and stewardship (for climate adaptation and mitigation), and economics (for farm profitability and social equity).

Such an extensive database may also allow us to tease confounding factors apart and present and contextually recommend soil health practices. The SHC encompasses all interdependent components and steps in soil health management and acknowledges the inherent challenges in promoting and sustaining soil health practices. Particularly, it emphasizes the necessity of bridging the relationship gaps between practices, SHIs, and soil function benefits.

The manuscript can be downloaded at Soil health cycle (unl.edu)