Lincoln, Neb. —Bob Harveson embarked on his career as a plant pathologist in the mid-1980s, which in 1999 took him to Scottsbluff as a specialist on the faculty at the University of Nebraska Panhandle Research, Extension and Education Center.

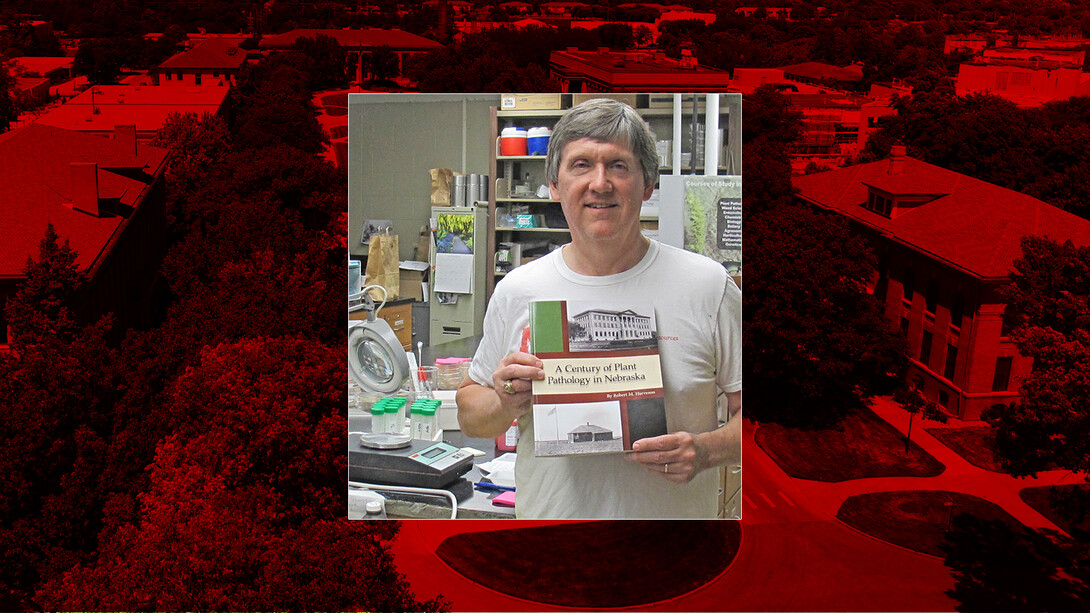

But before switching to science, Harveson earned a bachelor’s degree in history, and now the two interests are coming together in the form of a book he has authored, “A Century of Plant Pathology in Nebraska.”

The 114-page book was published in December 2020 by Zea Books of Lincoln (published by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries). The publication date coincided with the centennial year of the UNL Department of Plant Pathology.

The book includes numerous photos from throughout the past 100 years, as well as a number of line illustrations by Shara Yumul, who did the book design.

The front- and back-cover photos capture the Department of Plant Pathology’s beginnings and present – on the front are 1910 photos of the Plant Industry Building, the initial home for Plant Pathology, and the Scottsbluff Experimental Substation, the forerunner to the Panhandle Research and Extension Center. The back cover shows 2019 photos of Plant Sciences Building in Lincoln and the Panhandle Center.

Inside, the book presents 31 articles divided into five sections: the UNL Department of Plant Pathology, Panhandle Research and Extension Center; Corn, Wheat and Alfalfa; Dry Beans; and Sugarbeets.

The first article consists of a chronological list of significant advancements, discoveries or honors in plant pathology history in Nebraska, and the second article is a profile of Charles Bessey, the noted botanist who came to Nebraska in the 1880s as a botany professor, but went on to serve in several dean positions and chancellor of the university. One of his contributions was to strongly advocate for a department of plant pathology.

“I wanted to document the department’s birth and development as well as historically look back on its growth and accomplishments over the previous 100 years of existence,” Harveson writes in the preface.

Harveson traces the original idea for the book to 2010, when the Panhandle Center celebrated its centennial. For that event, a book was printed on the history of the center and the development and highlights of the various program areas. Harveson wrote the article on plant pathology.

“This event catalyzed my interest to research and write additional, similar articles on plant diseases in Nebraska,” he wrote. “Due to my life-long passion for history, this has been an enjoyable, cathartic escape from everyday duties, commitments and stresses.”

“To me it was a no brainer that I was interested in history and plant pathology, so why not work on the history of that particular discipline,” Harveson recalls. “There’s not a whole lot of us in the United States. I know of one other guy that does this kind of thing.”

Since 2010, Harveson has written dozens of articles sharing stories of discoveries in the history of plant pathology, both in Scottsbluff and more broadly in the Department of Plant Pathology in Lincoln. These appeared in news media, professional newsletters, and grower-oriented commodity magazines. Reworked and updated versions of these articles make up about half of the chapters appearing in “A Century of Plant Pathology in Nebraska.” He also wrote an additional 12 to 15 articles in 2019 and 2020.

Harveson notes that his book is not all-inclusive, but rather a collection of essays on selected people, diseases, and historical events involving agriculture and plant pathology in the state since the 1880s. He acknowledges previous department members who have recorded the department’s earlier past, including Robert Goss, Mike Boosalis, and Stan Jensen (who wrote the book’s foreword before passing away in late 2020).

Harveson has been at the Panhandle Center since receiving his Ph.D. in 1999 from the University of Florida. He received a master’s degree in plant pathology in 1989 from Texas A&M University, a bachelor of science in plant and soil science in 1985 from Tarleton State University in Texas, and a bachelor of arts in history in 1983 from Trinity University in Texas.

Although his first bachelor’s degree was in history, Harveson realized his job prospects in that major were not great, and he did not want to sit behind a desk in a coat and tie. His interest in applied science came from a member of his church who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resources Conservation Service).

He took the additional classes necessary for a bachelor of science in agronomy and soil science at Tarleton State University. A class in plant pathology led him to apply for a graduate assistantship in plant pathology at Texas A&M University and the beginning of his present career. Completing his master’s degree there and a Ph.D. at the University of Florida led him to the position with UNL in Scottsbluff in 1999.

The world has changed since 1999, and so has the field of plant pathology.

“It has become much more molecular,” Harveson observes. When he started, the standard diagnostic test for the rhizomania pathogen in sugarbeets was ELISA, for Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Although still useful, he said ELISA has become dated and replaced by PCR, for Polymerase Chain Reaction, a method now widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample to a large-enough amount to study.

Harveson’s appointment is 50 percent research and 50 percent extension, and he observes that there’s no bright line dividing one from the other. He operates a diagnostic lab at the Panhandle Center, works with producers to solve disease issues, and presents updates at field days and similar events. “The way I approach my job, it’s hard to tell where research ends and extension begins.”

Harveson sees potential audiences for his book as people with an interest in plant pathology or agriculture, and a connection to Nebraska. They also will be given to graduate students as they graduate. He says his book might serve as a reference for people who want to carry on the plant pathology story into the future.

Anybody who is interested can call Harveson at the Panhandle Center or pick up one at front desk of Panhandle Center. There’s no cost, and he has been sending them to people who are interested.

Harveson expects to work for awhile at the Panhandle Center, and says new plant diseases or needs for research tend to emerge every five years or so. They shift his focus to new areas, although he continues to build on the work he’s been doing for two decades.

He also expects to continue to writing about history. He has a number of sources available for historical information, including a personal library of sources at home and access to the internet and college libraries on line. Writing is a good counter-balance to the challenges and stresses in his professional life.

“It’s my way of escape. A lot of people would consider it to be work but I enjoy doing it and I learn so much from it. I just enjoy writing and doing that sort of thing.”