Lincoln, Neb. —Big stakes are involved in keeping plants safe from disease and pest assault. Each year in the United States, the damage and control costs from non-native plant pathogens total an estimated $21.5 billion. Meanwhile, the volume of plants entering the U.S. via ports is staggering — an estimated 2.8 billion arriving yearly.

At the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, the Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic provides inspections vital to protecting the state from plant- and insect-related threats. In 2021, the clinic received more than 1,700 physical samples involving plant diseases, insect infestation or nematodes. Phone and email questions to the clinic totaled 674.

Samples to the Husker diagnosticians cover a remarkable range. On one day, the clinic may receive corn leaves from a multimillion-dollar agribusiness needing to meet a tight sales deadline. On another day, a worried homeowner may bring in his struggling tomato plant. Some inspections are needed under regulations from the Nebraska Department of Agriculture; others, for a business order to proceed.

The clinic’s work makes a difference in multiple ways. Once the findings are complete, Nebraska farmers can make informed decisions on pesticide use. Large-scale plant shipments can move forward to meet business deadlines. Nebraska export sales can proceed to foreign markets. Nebraska agencies can be alerted to potential encroachment of plant diseases and destructive insect pests from other states. And a homeowner can receive answers about the leaf blight on her strawberry plants.

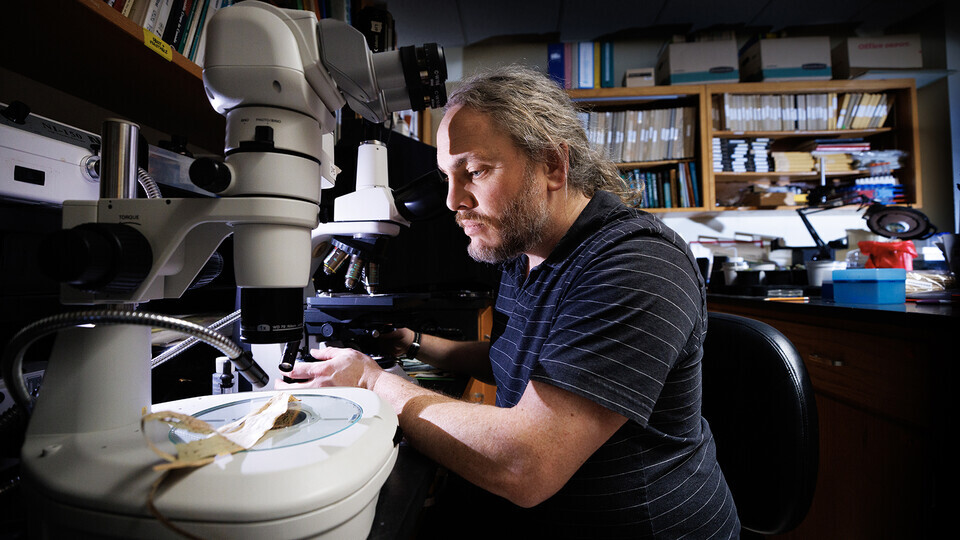

Craig Chandler | University Communication and Marketing Kyle Broderick, coordinator of the Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic and an assistant extension educator in plant pathology, holds a fescue sample with fungus growing on its roots.“I have a great group of scientists I work with,” said Kyle Broderick, the clinic’s coordinator and an assistant extension educator in plant pathology working out of Plant Sciences Hall. “It’s very important that I have a network I can reach out to,” given the need for specialized knowledge in scrutinizing particular samples.

The clinic’s transdisciplinary team includes Broderick in plant pathology; Kyle Koch, entomology; Chris Proctor, weed science; Terri James, horticulture; and Cheryl Dunn, UNL Herbarium. In addition, the clinic works with Nebraska Extension specialists and Husker scientists, including Tom Powers for nematode identification and Hernan Garcia-Ruiz for virus detection.

The Husker clinic is part of the National Plant Diagnostic Network, made up of a set of regional groupings. Nebraska is in the Great Plains Diagnostic Network, which includes an area from Montana south to Oklahoma. But because Nebraska’s environment varies so significantly from west to east, Broderick also stays in contact informally with the North Central Plant Diagnostic Network, which includes an area from Iowa eastward to Ohio.

“While not an official member of the North Central Plant Diagnostic Network, I’m invited to sit in on a lot of their conference calls,” he said. “When they say, ‘Hey, we’re seeing this disease in corn show up,’ I know to be on the lookout for it.”

An example is tar spot, which afflicts corn. The disease was first identified in 2017 in Indiana and has been moving west across the nation’s Corn Belt.

“Because I was hooked up with the North Central Network, I was better able to track some of that movement and talk to the different diagnosticians about where it is found,” Broderick said. “Last year, we finally confirmed it in Nebraska, and I was able to reach out to my counterparts at Iowa State. I told them: ‘This is what I’m seeing under the microscope. I really think this is tar spot. Can you confirm?’ They were very quickly able to say, yes, it is.”

Craig Chandler | University Communication and Marketing A collection of cactuses awaits its turn in the Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic.Another important monitoring tool are the samples of insect pests collected via Nebraska Department of Agriculture surveys. The clinic’s analysis of the samples helps determine Nebraska’s potential for new plant disease encroachment. For example, Nebraska does not yet have any confirmed instances of thousand cankers disease, a serious fungal threat to black walnut trees, but the Department of Agriculture’s pest traps have provided insects the Husker clinic has identified as the vector leading to the disease.

The majority of samples sent each year to the clinic are relatively straightforward crop-related items, such as spotted leaves on corn or soybean. But that still leaves room for occasional surprises. Sometimes requests arise from heartfelt personal concerns.

Years ago, a man brought the clinic large branches from cherry trees that were in bad shape and near the end of their lifespan. Broderick was struck by the man’s intense dedication to the plants. The man explained why: During the late Soviet era, he had fled Ukraine in the middle of the night. In one suitcase, he included three seedling trees.

“He smuggled these trees out of Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe into the United States and planted them,” Broderick said. “They were one of the few things that he had from back home.”

Another time, a woman brought in a rhubarb plant suffering from bacterial soft rot. The woman had received the rhubarb from her grandmother.

“It was from her grandmother’s rhubarb patch that had been going for probably over 60 years,” Broderick said.

The struggling plant “was one of the few things she had left from her grandmother.”

The diagnostic lab not only connects to Nebraska’s economy. It also can connect to Nebraskans’ hearts.